‘When I was a schoolgirl, and a great reader, some of my teachers used to remark on my essays and encourage me to become a writer. Decades later, and over the course of twenty years, I would at last be able to write the story of my and my sister’s childhood and its consequences, a must for my sanity and the sake of truth. This was my life’s battle, hard and very painful to face, but helped by writing THE PROMISE, a positive and universal proposal for all children.’

Books ordered through this website

are SIGNED copies.

To buy The Price of Silence for £14.00, postage included, UK only

To buy this book in Europe only (£22.85 postage included)

Outside Europe, prices on application.

R E V I E W S

Path through the pain , An engrossing and sometimes harrowing account of growing up under the dark shadows of child abuse. What happened to Hélène and her little sister in infancy haunts them throughout their adult lives as they struggle to find meaning in their relationships. But THE PRICE OF SILENCE shows that the healing of time and new generations of love can clear a path through the fog of pain.

(Peter Warren)

A brilliant book about a devastating story. This is a page turner set in France and London (where the author now lives) that got me really immersed in the story of two sisters and their abuse.

This story does shine a light on memories that cut through a culture of silence and a deliberate attempt to not see and forget.

It’s beautifully written and best of all, the author ends with her ‘Promise’, which gives me and any other readers real and positive actions to take, to try and prevent other children from meeting the same fate. It’s all very well feeling moved by a story but if we’re going to truly change things for kids and make our society a better one then each of us should do something to improve it.

Top marks for a fantastic read and a way to make a difference!”

(Gabriella)

I couldn’t put this book down – heartbreaking as some of it is, I wanted to know more and felt by the end that I had also learned a lot.

Having grown up with her sister in a lawyer’s family in postwar provincial France, followed by a life mostly lived in London, the author shows clearly how what appears to be a normal upbringing without any obvious cruelty can nevertheless have a profound influence on a person’s whole life when sexual and emotional abuse have been present

This is a courageous book and it is to Pascal-Thomas’s credit that she has fought to understand the ways in which her life (also that of her sister) has been warped by her childhood experience, and she is now seeking to transform this awareness into a force for good in reminding us of the rights of the child and suggesting appropriate rituals to help embed these rights into our lives and culture.

This book stands alone as a fascinating and involving read, informative and thought-provoking. It is also a worthwhile addition to the existing literature on childhood abuse.

(Sonia Upton (Counsellor))

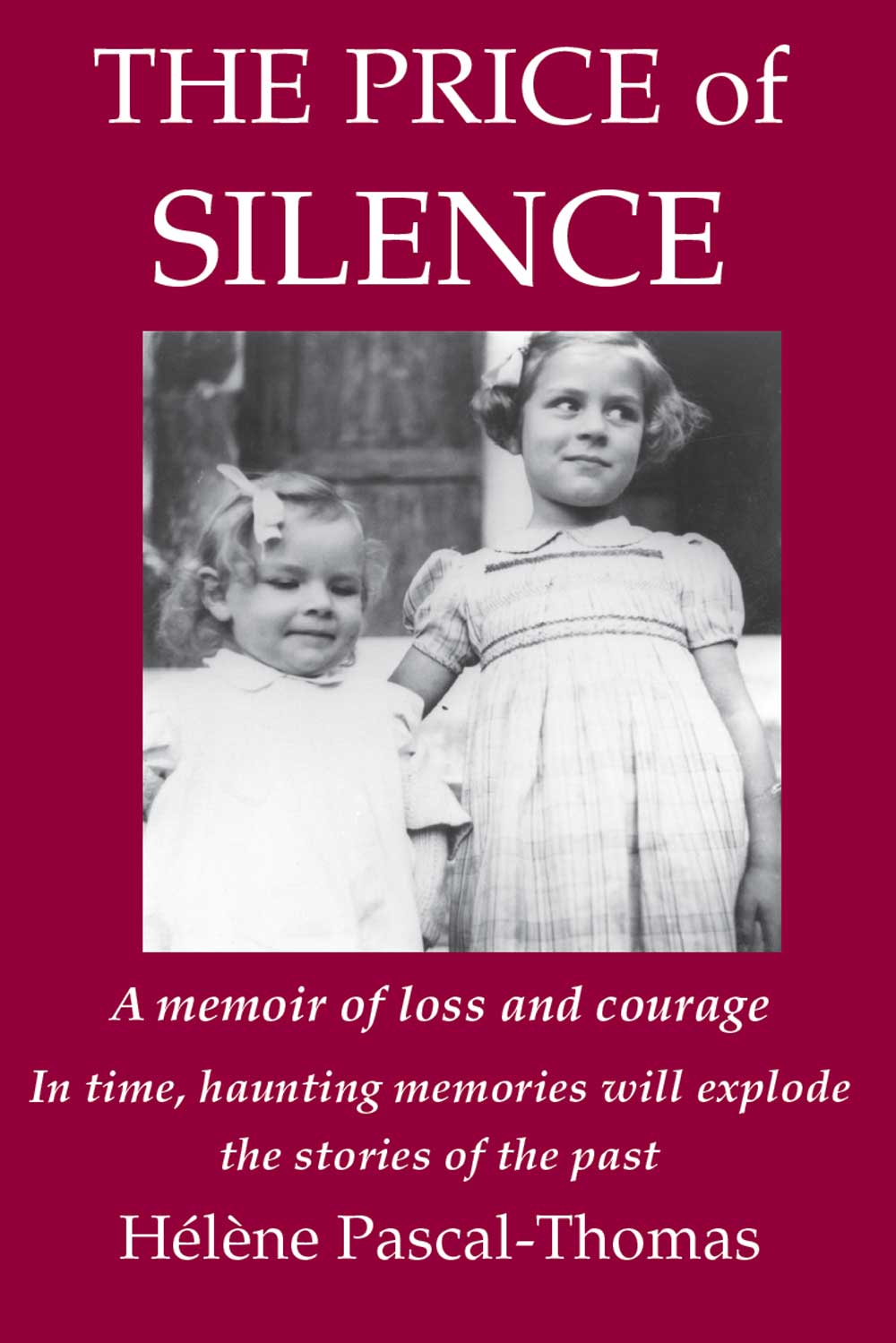

THE PRICE OF SILENCE

(TIVOLI BOOKS)

- By Hélène Pascal-Thomas

CHILDHOOD IS A TIME WHEN WE DON’T KNOW WE KNOW

How does it feel when, in the middle of your life, you come to the shattering realisation that you and your younger sister were sexually abused as young girls? How, having endured years of tragedy as a consequence, do you come to terms with uncovering a trauma that had confused and disempowered you? And what the effect on a woman trying to make her way in the world when so much of what it means to be a woman has been taken away? One writer’s unflinching struggle to make sense of her life, THE PRICE OF SILENCE answers these and many more searching questions in a courageous and heartfelt attempt to dissect what took place and bring the crimes to light.

PAIN HAS TO BE A TEACHER OR ELSE IT IS NOTHING

EXCERPT

REVIEWS

LESLEY ROBB (EDITOR)

Sometimes a book can put into words the feelings that have haunted peoples’ lives. For anyone who has suffered the physical and emotional pain of child abuse and experienced a lifetime of flashbacks, this is invaluable reading.

Pascal-Thomas was born just as war was breaking out in Europe. Her prosperous middle-class home in South West France should have offered her and her sister the safety and security every child deserves.

Instead, Pascal-Thomas realised in the middle of her life, that her lawyer father had sexually abused her and lent her to a friend (of his). Her mother closed her eyes to this horror.

It is a book that shocks, questions our memories and highlights the cruelty that can lie behind the closed doors of respectable society.

But this is not a misery memoir. It is a book of hope, positivity and grit that concludes with a challenge to us all in The Promise, a ceremony where we pledge to provide every child with the care, respect and protection they deserve. Do read THE PRICE OF SILENCE. It can be harrowing, but it’s an honest portrayal of a woman who lost so much in childhood, but has fought hard to face up to and break those chains that bind her to her painful past.

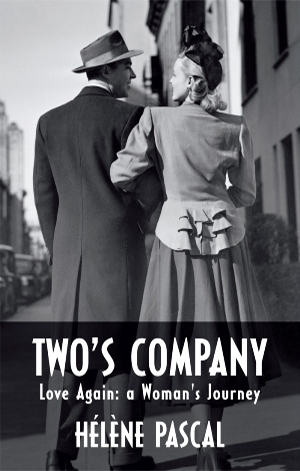

TWO'S COMPANY

(Tivoli Books)

- By Hélène Pascal-Thomas

“Two’s Company: Love Again, a Woman’s Journey” is a considerable addition to books on dating, being about meeting seniors: it relates my attempts, some funny and others tragic, to find love again at the age of sixty-six through the personal ads. Hope, fortitude and humour were qualities very much required.

As well as describing my ‘adventures’ , “Two’s Company” reflects on solitude, ageing, yearning, and also childhood, the time in our lives when, for good or ill, we learn about love and relationships.

I wrote TWO’S COMPANY in order to give myself a break from THE PRICE of SILENCE which I had started years before, as it was too painful to face up to my past for any length of time.

My daughter had gone to University and I felt I should not remain alone

A few words about:

THE NEW SEASON OF LOVE

A WORLD -CHANGING PHENOMENON

YOU COULD CALL it the silent event: it doesn’t make any noise -it’s not government policy!- as it stems from very private feelings and needs. It’s a new kind of mating season, but without the breeding compulsion, and without the often inconsidered impatience of youth. It is, rather, with the considered impatience of those who have learnt that time is finite, and precious.

WHEN SENIORS FIND themselves at that junction in their lives, faced with twenty or often thirty years in retirement, they are jolted by the realisation that they could have a life all over again. Besides, loneliness looms large if their marriage has become unhappy. They may have nurtured dreams of starting a new venture, taking up a hobby, travelling, but particularly, holding a prominent place in their new firmament: finding happiness again in a new relationship.

AS A MILLION MORE seniors join the internet each year, many in order of finding a new partner, you know that the new welcome demographic of people living longer, having healthier lives, and often with the means to travel and enjoy leisure, has been transformed by the shocking and world-changing feature of the new prospect of Love Again.

EXCERPT

I WAS A LITTLE tired of all this, a little dejected. I had occasionally thought of throwing in the towel, this search appearing at times futile and possibly hopeless. I put my tea down on the table by me and took in the peaceful orangery I was sitting in, the warm colours, the small couch furnished with multicoloured cushions covered with old Japanese fabric; the large paintings on the walls and the small Art Deco side tables; the enveloping cream-coloured armchair I was in by the window and the long cherry wood table I could write at: some files were piled up on one side, a golden lamp stood on the other, and if I put a thick cushion on the chair in front of it I was then able to work as well as properly own this space, the birds and the squirrels, all this belonged to me… By the right foot of my chair, near the secateurs and my somewhat muddy garden shoes, was a bag of seeds I kept there for the birds, and raisins for my familiar blackbirds: everything was relationship.

I WOULD LIKE to tell him, THE MAN, whoever he may be, that I went to the cinema yesterday to see an Australian film, and since the afternoon was devoted to pleasure, bought one hundred grams of jelly beans, loose, from the sweet counter, to be savoured with the relish of guilt during the performance; they were in fact devoured by the end of too many trailers… Then I nearly fell asleep a quarter of the way through but startled myself into alertness to rejoice as the film finally bloomed… I had an unusual glass of wine on my return, being normally sober in deed if not in thought, and lost myself in contemplation of the outlandish purple gladioli on the mantelpiece: could I tell him how I had changed my mind about gladioli? I had judged them pompous and arrogant in the past, so sure did they seem of their nobility. Supercilious, they looked down on you -a lower class of being- ever aspiring to sublime height and style, as if human fingers should remain low on the stem, never to soil the aristocratic silk …until one day my friend Marianne painted their portrait and I understood the other subtler features, the natural grace, the spiritual elegance, the individual striving of each single bloom to join in the slowly developing climax …so there they were, in my living-room, understood and appreciated. Five stems for ninety-nine pence at Morrison’s.

I COULD TELL him the cat had to have five teeth removed the other day and looked poorly and sorry for 48 hours, until he found his appetite again and finally enough lust for life to bring in a garden mouse that he played with all night, keeping me awake. I didn’t mind, I thought it funny, I was happy for him if not for the mouse which I managed to catch in the morning, right from under his nose, and release in the middle of the garden, under the ivy…

WOULD HE BE interested to know that I was planning a trip to Edinburgh now the festival was over, by myself for once, which I am normally loath to do – to see an exhibition of sculpture by Ron Mueck? I was in awe of Mueck’s work which I had seen previously in London two years before, the way that, not quite a plagiarist, he presented the human body on either a vast or minute scale but intimately, provoking a stunned contemplation of ourselves. I would go by train, with a good book, find myself a reasonable hotel, and take the two days as they came. It would be my first visit to the city in forty years, since my ex-husband Paul’s first exhibition at the Traverse Gallery, which allowed us to spend a long week-end there. We were just married and so called it a honeymoon, although there was no sex, but that is another story. It was freezing and we had to keep putting money in the meter slot in our hotel room to stay warm. There was no slot for Paul.

COULD I TELL him I’d visited my G.P. recently because of having felt dizzy on a few occasions? I had known my doctor for well over twenty years and had stuck with him in spite of moving areas because we liked each other and I respected him in spite of his grumpy moods. I had been concerned that my dizziness was age- related or a symptom of something dire, but he reassured me, mentioning my inner ear. Would I dare say that, as he examined one ear, his other hand gently and deliberately cupped my other cheek, which I noted was unnecessary but tender, and so I welcomed it, almost closing my eyes? I might tell him I had looked again at my book on Magritte’s, to be entertained at first, but led to wonder if his work, as the other Surrealists’, hadn’t been the by-product of the First World War, a time when familiar reality had been so shattered, its centre of gravity exploded, as to be judged incoherent and represented as such. Peoples who haven’t lived through such disintegration never need step into the absurd, do they? What did he think? He. Him. Who didn’t sit at my table or hold my hand, who didn’t talk to me. Whose place was empty in my bed. Whose absence left me cold all over…

IMAGINING, IF NOT anticipating, being in love again filled me, simultaneously, with a nervous anxiety similar to fear of flying, a balloon released to unknown winds… I knew that I could again lay myself open to exploitation and betrayal because I was (we are?) when I loved, childlike: love is childlike, child’s play, all that appears is a given, and then… A large sticker across my heart warned: FRAGILE. It was the same with friendship, allegiance: there had been the visit to my flat once- at my invitation- of Tina, the psychotherapist who had been my supervisor during my training as a counsellor. I had great regard for her subtle judgement and insight and she praised my work at the time, which made me feel valued. I had gone to her for help, three years previously, at a time when I had felt at my lowest and needed to pour my heart out to a witness who not only knew me but understood what I was going through. Her subsequent visit a year later had been my opportunity to show her how well and full of energy I now was, and the healing comfort I drew from living in a wonderful place full of light and views on beautiful trees. We had tea, chatted amicably, I was keen to show her that I was now better equipped for happiness or at least contentment, that I felt I had a future at last. When she got up to leave and I opened the front door for her, she stopped on the doorstep for a moment, looked at the steps that separated my flat from the pavement above and said: -These will be difficult, soon. Still, you won’t need to go out every day…

THE NEXT MESSAGE I listened to on my voicemail belonged to Mick, six foot three, green eyes and fit, a retired graphic designer who for thirty years had his own consultancy and now worked from home, as he pleased. He was divorced with two girls of twenty-two and twenty-seven. He enjoyed the good things in life, eating, cooking, travelling, and now did a bit of painting and visited galleries. He also liked films. He used to play rugby but had now converted to golf. He took occasional holidays. What he wanted was someone to share all these things with: his voice, on my voice mail, had risen to capital letters, “to SHARE these experiences”; his loneliness reached me, echoing mine. So I was sitting again at the terrace of “Bruises” that September Wednesday morning, when I saw Mick crossing the road at the pedestrian crossing exactly opposite me. He had exclaimed, when we spoke on the telephone and decided to meet:

– I know! I shall wear my striped t-shirt, very colourful, vertical stripes of blue, red and cream, you can’t miss me in that!

IF IT SOUNDED like a flag, I was pleased at the thought of an older man in a t-shirt, better than a three-piece suit any day, this wasn’t a gentleman’s club occasion; I welcomed the fact that he was six foot three, I like tall men, and I didn’t mind ‘follically challenged’; slim with green eyes and fit-looking would do fine.

WE SMILED AS we shook hands, and I swallowed hard in astonishment: I had before me a younger version -he hadn’t mentioned his age but I suspected we were contemporaries -of my daughter’s father, David, who was thirteen years older than me, which made him eighty now. I no longer talked about him and would hate him more if I despised him less, for his shallowness and cruelty, his total lack of a moral code and complete indifference to the consequences of his actions. I had for many years forbidden him access to my home since, a long time before, having to save myself from him and my unhealthy passion. Only my daughter sees him, seldom, reluctantly and dutifully.

DAVID’S EYES; his mouth nearly, the way it shaped almost into a beak on pronouncing certain sounds; his colouring and height; his bald head and side hair… The nonchalant manner he had as he walked, crossing the street, which belonged to tall men at ease with their bodies; the way he sat, wrists resting on his knees, rocking slightly as he spoke. There was a man called Mick underneath all that… I had to find out about Mick, I had to be reassured.

REVIEWS

BUY

Two’s Company: Love Again: A Woman’s Journey,

Please use the following Email Address to place an Order:

BUY

The Price of Silence

Books ordered through this website are SIGNED copies

Please use the following links to place an purchase:

Books ordered through this website are SIGNED copies

Outside Europe, prices on application.

Any difficulties please contact

Amolibros

Loundshay Manor Cottage

Preston Bowyer

Milverton

Somerset

TA4 1QF

Tel 01823 401527

THE TIMES INTERVIEW

‘Sexy- Generians: The over 60s still in search of love.’ Valerie Grove :‘THE TIMES’ interview. Click here to read the Times interview 15.08.11

MATURE TIMES INTERVIEW

‘Granny is dating – get over it…’ – Jane Silk ‘MATURE TIMES’ interview of Helene Pascal was short-listed for THE ROSES MEDIA AWARDS 2011.

Interview – ICI Londres Magazine – Click here to read this article in French